Malaysia’s second-longest river, the Kinabatangan, and its surrounding floodplain forests, are two exquisite ecological gems constituting the jewel-studded crown of Borneo. I was grateful to spend two nights exploring this incredible ecosystem on my March 2023 Borneo trip.

The Kinabatangan River possesses an ecosystem so bountiful in wildlife that it is often marketed as ‘Asia’s Amazon’. The spectacular gallery forests lining the river are a final refuge for the island’s most iconic species; namely, the Bornean Orangutan, Rhinoceros Hornbill, Estuarine Crocodile, Bornean Elephant, and Proboscis Monkey. The Kinabatangan is also one of only two places on Earth with ten or more primate species coexisting together, and is home to over 300 species of birds. I set myself with the task of spotting a wild Bornean Orangutan as well as a male Rhinoceros Hornbill during my two-night stay along the river. I’d dreamed of seeing both species in the wild from the time I was 9 years old, and was finally able to seize my opportunity to see these emblems of the Bornean rainforest for myself!

On a different note, I can’t recall ever visiting an area as biologically rich as the Kinabatangan that was so threatened by human activity. The region’s rainforests have undergone near-total destruction as a result of the ludicrous palm oil industry. But more on this later.

After my family’s excursion to the sanctuaries of Sandakan, I was seriously looking forward to the Kinabatangan. For half my life, I’d dreamt of visiting the river and searching for its majestic wildlife. This desire had only grown larger from the time I decided Southeast Asia would be my future stomping grounds as a zoologist and conservationist.

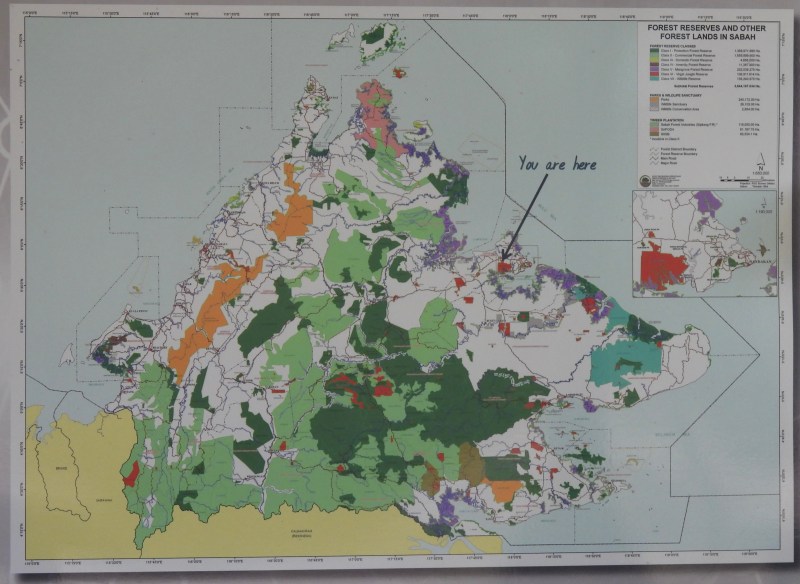

The densely forested delta of the Kinabatangan, with its countless channels, is cloaked in hundreds of square miles of protected mangroves. Farther up the waterway, marvellous riverine Dipterocarp forest replaces the mangroves. 28,000 hectares (~110 sq miles), or about the same land area of Fresno, California, is protected along the lower reaches of the river within the Lower Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary. Established in 1997, the protection came at just the right time to preserve the very last interconnected fragments of forest along the river’s edge. Unfortunately, this highly unique ecosystem is still imperilled, as I would later see with my own eyes.

Standing on Sandakan Pier, luggage beside me, I eagerly awaited my entry into possibly the finest coastal wildlife habitat remaining in Southeast Asia, visible as a thin strip of green across Sandakan Bay. A speedboat was on its way that would take us 20 or 30 miles upriver to our lodge, nestled deep in the sanctuary near the village of Sukau. Idling at the pier, we met a friendly American family that was voyaging to the same place as us. Max, a nature enthusiast, planned their weeklong Borneo trip, accompanied by his wife, aunt and mother. I spent a lot of time talking with Max over the next few days, and we did some wildlife photography together around the lodge.

The speedboat ride was long, refreshingly windy, and mesmerising. While most of the other tourists aboard dozed or passed the time on their phones, I intently observed each aspect of the ecosystem. I watched the landscapes change from constricted channels of mangroves near Sandakan, to the river’s estuary which spilled into the Sulu Sea, to swathes of Nipah palm, and farther on, lush walls of extensive rainforest. I’d been self-studying this river for years and was impressed by the sheer amount of forest there was lining the banks.

However, much of the forest I was seeing was merely a facade. The protection provided by the sanctuary only covers strips of rainforest along the river, and past that is an endless monoculture of oil palm. A thin veneer of greenery hiding endless plantations behind it. And as I would later see on the way to Sukau, not all plantations were established away from the river–quite a few we passed by were situated directly above the flowing water. It was then that I realized just how dire this situation is in the region.

Plantations that reach the riverbanks, like the ones I saw that day, not only degrade but fully destroy the already highly fragmented ecosystem by blocking wildlife from migrating along the Kinabatangan’s narrow ‘corridor of life’. Fewer wildlife migrating between areas of the forest means much fewer seeds being dispersed, and a high percentage of the 1,000+ types of plants in the region will eventually disappear as a result, along with hundreds of species of animals that depend on the forest.

The greed of the plantation owners here is shocking. They clear-cut everything apart from a thin ribbon of forest along the river’s edge, and even then they feel the need to destroy the entire wildlife corridor by planting all the way to the riverbank. And I’m sure many of the plantation owners are well-aware of the river’s importance as a wildlife sanctuary.

Given that an average palm oil plantation can be well over a dozen square miles in size, there is no good reason not to leave a tiny strip of rainforest intact along the river for the animals. It’s a serious issue that NEEDS urgent fixing if the Kinabatangan is to retain its biota!

Now that my environmental rant is over, I’ll move on to a more positive topic.

Never before have I been this deep into the jungle, and I honestly can’t even put words to how I was feeling cruising through thousands of acres of Bornean rainforest. Because it was the early afternoon, there was little wildlife about–also, when you’re roaring through the forest at the speed of a passenger car, you’re unlikely to spot much. We did stop for a medium-sized troop of Proboscis Monkeys near the river’s mouth, which were amazing to observe for the second time in the wild! I’ll save my description of these guys, which I nicknamed ‘probos’, for later—the reason being that we saw loads more of these endangered monkeys while on the Kinabatangan.

As for birds, they were few and far between due to the time of day and the speed we were going—this Lesser Adjutant was probably the most interesting find:

One thing that was apparent on the boat ride was the youthful age of the forests around the river. 50 years ago, nearly all the ancient Dipterocarp trees along the Kinabatangan were selectively logged, their trunks cut into sections and floated down the river to processing mills. Surprisingly, this destruction of the primary forest actually benefited many of the animals of the ecosystem. My Mammals of Borneo book explains that orangutans, deer, elephants, and many other herbivorous mammals thrive in secondary and logged forests. An abundance of leafy herbs, grasses, shrubs and fruiting trees that spring up with increased levels of light once the giant trees are removed provide ample food for these herbivores.

Bornean Pygmy Elephants in particular, who much favor herbs and grasses in their diets to woody plant material, thrive in dense, high numbers along the river (~150 total). Elephants are ecosystem engineers wherever they roam, a trait shared by beavers and humans. They directly form new habitats by intentionally trampling trees and shrubs and dispersing the seeds of their preferred food plants to these newly cleared areas by, well, pooping. Along the Kinabatangan, they strip flat areas near the riverbanks of woody vegetation, allowing thick grasses to grow, a favorite food of theirs.

They also control the population of another preferred food source, the invasive Water Hyacinth from South America, which floats down the river in weedy mats.

2 hours after leaving Sandakan, we passed the small riverside village of Sukau, on the fringes of one of the main parts of the wildlife sanctuary, and travelled 5 additional minutes upriver to our lodge. Located within dense rainforest, and built to have minimal impact on the surrounding ecosystem, Sukau Rainforest Lodge was the first ecolodge of its kind in Southeast Asia. From the time I first read about the conservation ethos of the lodge and its excellence both in accommodation and wildlife viewing, I knew we had to stay there!

While the sister company to Sukau Rainforest Lodge, Borneo Eco Tours, was pretty terrible with what it delivered for the price we paid, I’m happy to say that the opposite is true for Sukau. I highly recommend the lodge to anyone travelling to Borneo. If you want an authentic jungle safari experience in relative luxury, knowing that you’re contributing to the conservation of this irreplaceable ecosystem, then stay here.

We were greeted warmly by the lodge staff, and we marched in single file from the dock, across to the lodge’s main boardwalk (the entirety of Sukau is connected by elevated walkways). We continued on to Gomantong Hall, the main reception area, where we were briefed on the evening and following day’s activities. They served us each a refreshing cold drink made from a local plant called Pandan.

We made our way over to our villa after checking in, located on the other side of the lodge’s grounds. A cacophony of cicadas, birds and crickets was ever-present, as the lodge is nestled within verdant rainforest. After checking in, we had some time before our first afternoon river safari so I made my way over to Melapi Jetty, the main restaurant/bar/commons area, overlooking a picturesque bend in the river and a patch of forest.

One really cool thing about Sukau Rainforest Lodge: their buffet table is a creatively repurposed wooden boat that was used by one of my idols, David Attenborough, and his crew in 2011 to film a documentary around the Kinabatangan! It’s one of the few Attenborough flicks I haven’t seen yet, and one I definitely should watch.

As for their other design elements, the lodge is committed to serving the local community around the river, and most of their staff comes from surrounding villages. They source all of their decorations and building materials locally, which adds greatly to the aesthetic of all the buildings.

Our safari departed a little before sunset. Because we couldn’t choose what boat we were assigned to, we ended up with a rather mediocre guide who wasn’t particularly knowledgable about the animals we came across, and who often left the pointing out of wildlife to myself! We still enjoyed an excellent safari experience. Our first cruise was targeted at Proboscis Monkeys. I was apprehensive as I donned my life jacket and took my seat toward the middle of the boat. We drove directly across the river, this time via a silent electric motor, which allowed one to be fully immersed in the wilderness of the Kinabatangan. I split time with my binoculars (a must for safaris here) with my family members.

Our first troop of beautifully-adorned Probos was active and social, and our guide gave some basic facts about the creatures as we sat back and watched them go about their business. I managed some good shots of the females, but the dominant male was obscured by vegetation.

There are two relatively large ‘harem’ troops of the monkeys near the lodge, led by a Squidward-nosed alpha male, a characteristic feature of the species. Females and young of the troop have smaller, pointed noses.

Proboscis Monkeys have to be among the world’s most unique and bizzare mammals. They eat leaves almost exclusively and possess a cow-like gut to digest them; in addition, they are the only semiaquatic primates on Earth—adults have webbed feet and a valve in their nose that blocks the intake of water—and will often swim to cool off, socialize, or travel across channels to new feeding grounds. In the Kinabatangan Floodplain, the large population of crocodiles keeps the monkeys in the trees for the most part.

We travelled upriver, then down a tributary of the Kinabatangan to our second troop, which was making preparations for the night in the canopy of a tree. This time the alpha male was in full view, and actually looked down at us!

Though male Proboscis Monkeys are certainly quite large and reach twice the size of females (they can weigh 60 pounds), other features besides just body size are key to determining the harem-leading alpha in Probo society. This is unlike other primates, where the alpha is often determined by physical strength and size.

Nose length in Probo society is of upmost importance, wherein the bigger it is the better. Big noses are a sign of good health. The dimensions of another bodily appendage are also important in determining who’s boss—I’ll let you figure out which one I’m talking about.

All in all, sporting their big guts, bright red ‘packages’, and huge noses, alpha male Probos manage to be majestic and goofy-looking at the same time. Such a cool experience viewing these Bornean endemics in their natural habitat!

We saw a couple other animals on this particular safari. In terms of non-Proboscis Monkey mammals, we saw number of Long-Tailed Macaques, a highly abundant species in the region, and a few Southern Pig-Tailed Macaques. A Blue-Eared Kingfishers and two Oriental Darters constituted the birds we saw.

By the time we’d returned to the lodge, dusk was falling. We relaxed for about an hour after our safari, and headed over to dinner. Our family friends from Singapore were spending a couple days at Sukau and we wanted to have dinner with them on their last night. They’re a couple with two boys, and the mother is friends with a National Geographic wildlife photographer I’m in contact with.

Dinner was delicious, served on the buffet table at Melapi Jetty, and included many Malay specialties, prepared with fresh, local ingredients. During dinner, the lodge’s safari coordinator approached us, then asked our table if we’d be up for a night safari. It was an immediate “yes” from me, my sister, and the other family, but my parents decided to skip the tour for that night and get some rest instead.

If you want an all-around wildlife experience on the Kinabatangan, night safaris are a MUST. A large percentage of the creatures surrounding the river are primarily nocturnal, including sought-after specialties like tarsiers, civets, slow lorises, clouded leopards and owls.

At 8pm, a little while after dinner, we jogged down to the dock and boarded our boat. Our guide for the night cruise wasn’t too talkative, and this only added to the experience. He was knowledgable about the animals we came across, a great spotter, and left us in silence to observe wildlife on the riverbank illuminated by spotlight. This was a pleasant contrast to the broken-english droning narration of the Kinabatangan’s critters (often the ones I spotted!) we got from the other guide.

Our first species happened to be a Buffy Fish Owl, right next to the lodge….. the bright beam of the spotlight and the confidence of the owl made for a pretty surreal wildlife experience. Though I’d recorded this species before in Singapore, seeing owls in the wild never gets old!

Our next animal was an exciting find—a mammal, and a carnivore at that, possibly endemic to Borneo. Depending on the taxonomic splitting of the civet we saw, it was either a Small-Toothed Palm Civet; a widely distributed species around Southeast Asia, or a Bornean Striped Palm Civet, a Bornean endemic. Farther DNA analysis and anatomical comparison is necessary to determine its status as a true endemic species or just an insular subspecies. Either way, watching the civet’s antics as it foraged for fruit within the crown of a tree was cool.

I could go through each additional species we saw chronologically, but I feel this would take way too long. So I’ll just break down the rest of my finds by taxonomic class (mammals, reptiles, birds).

Throughout the hour-long safari, we were all absorbed in the truly awesome experience of wildlife spotting on the river at night. We headed upriver probably a mile (2-ish kilometers) into the wildlife sanctuary proper, where it was cool, refreshingly misty, and the only thing visible beyond countless stars was our spotlight beam.

Mammals we noted include this Large Flying Fox, a truly massive species of bat that is frugivorous (fruit-eating) like the civet:

The birdlife at night was just incredible. We saw kingfishers, Pied Fantails, and other fast and weary diurnal birds sleeping on branches. They didn’t move when the spotlight was shined, and we were able to manoeuvre the boat right up to them. This allowed for seemingly unnaturally close encounters with the birds…. to the point where you’d think they were stuffed museum taxidermies!

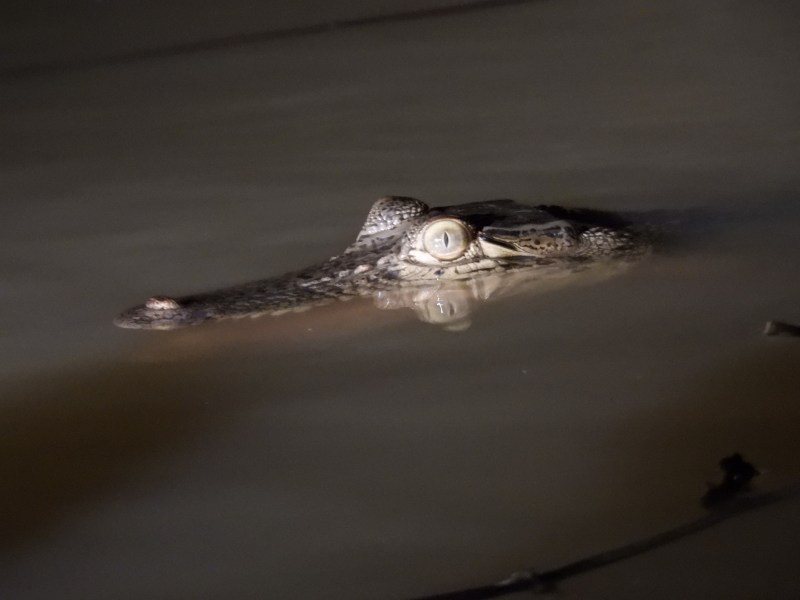

Scaly denizens on the prowl included baby Estuarine Crocodiles, bronzeback snakes, and a water monitor sleeping on a tree branch.

We were tired but satisfied after our night safari. Apparently one of the other boats happened upon an elusive slow loris, but I was more than happy with our finds. We said goodnight to our family friends and headed to our villa for a night of sleep that would be cut short by a 6 am morning safari…..well worth the 5 am wakeup though. The incessant croaking of frogs and chirping of crickets made for a vibrant jungle symphony as my sister and I headed into our villa.

Safaris aren’t quite my sister’s thing, and she opted out of the super-early-morning one. Too bad for her though–we nailed some awesome regional bird specialties.

It was pitch-black when we woke up, and the forest was relatively quiet. Near the dock, a single fluorescent light angled toward the water was a magnet for seemingly every insect in the Kinabatangan. A number of insectivorous microbats swooped around the light, gobbling mouthfuls of the bugs. As dawn broke, it illuminated the eerie scene in splashes of blue.

A crowd of people had gathered on Melapi Jetty by 5:45 am in preparation for the morning safari– my family was among them. We boarded the boats soon after, but as every other vessel gurgled away into the thick blanket of fog that smothered the river, ours had to wait a significant amount of time for two tourists that decided not to wake up early enough! Finally, after an anxious 20 minutes, we were off.

The river at this hour was refreshingly cool, and though the dawn was clear, the air was thick with mist. We ventured first to the probos from the evening before and spent some time watching the monkeys awaken, though I was personally more interested in birds this safari.

Upriver, our guide pointed out a spot where an elephant herd had trampled through weeks before. Here we saw proof of the elephants’ role as ecosystem engineers.

Early morning birding on the Kinabatangan was outstanding. As we cruised along, the region’s avian inhabitants revealed themselves one by one. Green Imperial Pigeons and Slender-Billed Crows flew across sections of the waterway, while hungry darters, egrets and kingfishers dotted piles of driftwood anchored to the riverbed. Swifts and swiftlets dominated the skies above the river, while hornbills called out from within the forest. It was a beautiful, tranquil scene, amplified by the brightening heavens and abundant fog.

Atop an old fig tree, a metallic-coated, benign Silvery Langur was surveying the river. Like probos, Silvery Langurs are part of the subfamily Colobinae (leaf-eating monkeys), and live in harem societies. The lone male we saw was a bachelor.

3 types on langurs live along the Kinabatangan, and all have similar diets and habits, which would lead the naturalist to believe the monkeys are in constant competition for resources. It’s true that where one species of langur is abundant, the others are rarely found– this is a proven fact of nature. No two species with nigh-identical niches can coexist in the same area. But the situation with these peculiar primates gets more complex than that.

Silvery Langurs dominate the trees dotting the riverbanks, their preferred habitat, and are the most common langur in the Kinabatangan floodplain. Through millenia of natural selection, which has favored certain genetic traits in their species in this particular habitat over the other langurs, they’ve pushed their counterparts deeper into the forest. This is why it’s uncommon to see either Maroon Langurs or Sabah Grey Langurs near the banks of the Kinabatangan.

The other two species are no longer in direct competition with Silvery Langurs: their niches now differ slightly. However, both maroons and Sabah greys live in the same habitat, have similar troop structure, share the same diets, but still manage to coexist. How? Two reasons. Where both species coexist, maroons forage in the upper canopy of trees, while Sabah greys take to the lower and middle canopies. This aleviates direct competition for food. The other reason is most surprising– the monkeys form coalitions with one another! When food is scarce and trees cannot be divided, they join forces and forage together. This not only promotes survival during lean periods, but also could be evidence that interspecific competition doesn’t always occur between two similar species.

Anyway, it’s a theory I’ve formulated through research and time spent along the river which I find fascinating.

About 40 minutes into our safari, we reached a point along the river where one side was oil palm and the other was unlogged, protected forest. Here, we were in for a surprise encounter.

As we cruised slowly along the bank, an unmistakeableWhite-Crowned Hornbill flew into one of the trees to join its mate. These guys are a regional rarity sought after by birders like myself. One of the only entirely carnivorous hornbills, they live in family groups that guard a large territory, and spend their days hunting through the forest like a winged pack of wolves.

As soon as they came, they disappeared, materialising into the depths of the forest.

We continued along, making our way deep into the jungle down a thin tributary of the river that leads to a famous oxbow lake, Kelenanap, known for its wildlife. There are few things as eerie as cruising down a narrow channel with the rainforest enclosing you entirely.

The lake appeared out of the foliage, sprawled out in front of us. It was surrounded entirely by lush, mature rainforest. By this time, the fog had burned off and equatorial sunlight was beating down, making it impossible to see without squinting. Our guide spotted an Oriental Honey-Buzzard flying off into the distance.

The highlight of the lake was a pair of Oriental Pied Hornbills. A male from across the lake sat perched alongside in a tall tree his mate, before both animals flew across the water body and into the jungle on the opposite side. It was a pretty cool sighting! Though we saw upwards of a dozen Oriental Pied Hornbills on the Kinabatangan, spotting them never gets old. The thick, helmet-like casques (basically a bony extension of the beak, located above the upper mandible) of males easily differentiate the sexes.

By this time, we’d been on the boat for about 2 hours, and the peak time for morning wildlife watching had ended. We made our way back to the river, and voyaged back to the lodge for breakfast. Our outing was a success!

We ate breakfast with our family friends, and saw them off as they caught the speedboat back to Sandakan. My diet was appalling throughout the Borneo trip, and I completely indulged my sweet tooth at every meal. The generous amount of treats provided by the buffet I piled onto my plate and rapidly consumed. After breakfast, I took some time to journal and sat by the river. The view of the snaking, silt-laden river inching its way to the sea and in the background seemingly endless gallery forest was beautiful.

Two egret-like birds soared overhead, and peering through my binoculars, I was curious to establish their species ID. They were large, primarily black, and had a orange bill and yellow eye-ring. Suddenly, I realized exactly what I was looking at– Storm’s Storks! Filled with anxious excitement, I whipped out my camera and took some shots of the birds before they disappeared out of view.

For you non-birders, you might not get why I was so excited to see these particular birds in the wild. But here’s why.

Of all the avian specialties of the Kinabatangan, there are few as sought-after as this one. This is because they are globally endangered, with a mere 500 remaining in the wild, in small and extremely patchy areas of wetland around Southeast Asia. The Kinabatangan is a global stronghold of the species, and is probably the only locality on Earth where sightings of the storks are reliable. What a find!

Afterwards, walking back to my room, I met up with Max and his family. They were photographing a striking Paradise Tree Snake on the lodge’s boardwalk that kept making an appearance. However, there was an obstacle in the way of me sighting this unique reptile.

An angry alpha male Long-Tailed Macaque (the boss around these parts) chased us a little ways away out of his vicinity before I could get a good view of the snake. According to Max’s mom, this guy had attacked the window of their villa and bared its teeth at them from outside! So, wisely, we waited a little while for the monkey to head into the forest.

For the next hour and a half or so, I enjoyed an excellent wildlife photography session with Max and his family. We saw two of Borneo’s most remarkable and bizarre reptiles, a Paradise Tree Snake and a Green Draco Lizard; species that evolved to glide.

The rainforests of Borneo and Southeast Asia as a whole are unique for their extreme diversity of gliding creatures, most of which are found nowhere else on Earth. 35 of the world’s 50 flying squirrel species are native to the region, along with the world’s only gliding frogs, lizards and snakes. Additionally, the best gliders in the animal kingdom–an entire taxonomic order of mammals, the colugos–are endemic to Southeast Asia.

I hypothesize that the reason why Southeast Asia is the global glider hotspot is due to its vegetation. Southeast Asian rainforests are the loftiest on Earth and are dominated by Dipterocarp trees. Dipterocarps are by far the tallest tropical trees, easily reaching 200 ft (60 m) when fully-grown. Canopy-dwelling wildlife must travel between these giant trees to feed, but the sheer size of mature Dipterocarps means distances between rainforest trees in Southeast Asia are much larger than in tropical forests of other locations.

Therefore, evolving an anatomy that allows you to glide between trees is a really good idea! Not only does it save a lot of energy while foraging, but it allows one to travel around the forest quite quickly.

We went our seperate ways–myself to the lodge’s pool, and the Omicks back to their villa–shortly after Max pointed out this gorgeous male Crimson Sunbird:

It was really cool nerding out about nature with Max, and I got to know his family a bit more as well. After swimming, I changed clothes and rallied my family to the dock. Our evening safari was departing an hour earlier than scheduled as a resolution for the lodge’s famous Attenborough Boardwalk being closed, where daily, hour-long tours are normally held. We were supposed to be tracking elephants upriver; and a few of the boats, including Max’s, actually saw the beasts on that day, but ours wasn’t so lucky .

Instead, we ended up sighting my primary target species for this trip– one so iconic and threatened, and an encounter so memorable, that I consider it among my top 3 wildlife sightings ever! I’ll save the details of the encounter and the species we saw for later, but what I will say is based on our luck from the beginning of the safari, I wasn’t expecting to have seen much.

3pm, our departure time, is a really bad time to be wildlife-watching on the river. It was blazing hot and extremely bright, and basically nothing apart from macaques were active. We were on our way to try and find elephants, but I was more keen on an orangutan. For over an hour, all we saw as we cruised upriver were troops of macaques, egrets and distant Oriental Pied Hornbills. Our luck wasn’t good, but I kept my fingers crossed.

Our guide made the decision not to follow the other boats toward the elephants, and instead turned around after about an hour and a half. Near a patch of tall grasses along the river’s edge was a young Estuarine Crocodile resting in the shade. Unfortunately, we saw no big adult crocos on the Kinabatangan, but we assuredly knew they were around. The juvenile crocodile we saw let us approach it quite closely.

My hopes for an orangutan sighting (or anything interesting, for that matter), were fading as we reached about the halfway point back to the lodge. We saw no new nests in the trees near the river, which would signify recent orangutan activity. I was preparing myself for sullen disappointment.

Suddenly, as we turned a bend in the river, a Sukau safari boat appeared near the river’s banks. All lenses and eyes aboard were poised toward the forest. I knew immediately what animal had been spotted, and our boat gurgled closer. I was shaking with anticipation! The trees rustled, and an orange-furred creature showed its characteristic face through the foliage– a female Bornean Orangutan and her baby!!

There are around 800 orangutans scattered along the Kinabatangan, and seeing one is considered 50/50 by the guides at Sukau. Seeing a mother and baby together right at the banks of the river is a way lower probability! My mouth agape, I passed my camera to my mom to take photos so I could fully absorb the encounter.

Bornean Orangutans are endemic to Borneo, as their name suggests, and are larger and have darker fur than their 2 cousins on Sumatra. The three species of orangutans were once grouped as a polytypical species of great ape, but were split into distinct species through DNA analysis relatively recently. All three are critically endangered and are teetering toward the brink of extinction. On Borneo, populations of the Bornean Orangutan have plummeted something like 60% in the last 30-50 years, and are projected to decline much farther. There are 50,000 wild orangutans left in Borneo; 11,000 of those in Sabah, which are puny figures compared to the million fiery-orange apes that once ruled the island’s lowland forests. Curse the palm oil and timber industries!

These incredible primates were cool to see at the Seiplok Sanctuary, but nothing, and I mean nothing beats seeing them in the wild. They’re way furrier than I expected, less humanlike, and their movement through the branches was both mesmerising and majestic. The female guided its baby up a shrubby tree to a branch overhanging the river, where she planned to build her nighttime nest.

First, she had to sort out her hunger, and for her dinner meant the hearts of rattan (a type of vine-like palm). Rattan hearts are an important food source to orangutans when ripe fruits, their main source of nutrition, aren’t available.

The female pulled herself into a position where she was very visible to us. We were no more than 20 feet (6m) away from her! Pulling rattan vines off the tree with brute strength, she delicately split them open with her fingers and dexterous lips, consuming the tender heart inside. Orangutans have deep ancestral knowledge of the forest that gets passed down generation to generation, and knowing it intimately is the key between life and death for the apes. The mother orangutan was teaching her baby how to make use of the forest’s bounty by demonstrating how to obtain the sustenance from the rattan vines.

In the roughly 7 years the baby spends with her (behind humans, the second longest child rearing period in the animal kingdom), she will teach it how to make use of over 400 species of plants for food, shelter, and medicine!

For almost half an hour, we watch the pair of orangutans intently. I held my breath in excitement, beads of sweat trickling off me with every movement the mother made. She moved positions and fed herself from a chair of leaves overlooking our boat. Everything around us apart from the mother snapping branches and rustling through the leaves was seemingly silent. It was surreal and incredible at the same time, watching the master of the Bornean jungle go about its daily business.

There are very few creatures as captivating as the wild orangutan.

The highlight of my Borneo trip made, our boat departed the orangutans after some time to make room for other boats from different lodges. Sukau’s excellent environmental ethos has led to them installing silent electric motors on all their safari boats. This not only makes wildlife watching easier and more pleasant for guests, but also avoids harming the animals through toxic diesel fumes and loud engine noise. Sadly, not every lodge along the river seems to share Sukau’s concern for the river’s ecosystem; more often it’s providing the cheapest possible safari experience to overseas tourists. The boats that replaced ours next to the orangutans were so loud and the fumes so smelly that the poor apes were forced back into the forest.

The insatiable greed of this region is sickening to an extreme. If organizations like Sukau didn’t exist to financially entice governments to protect Borneo’s natural wonders, the entire island would be a giant palm oil plantation. From lack of any concern for the wellbeing of wildlife to plantations hugging the river’s banks, it’s like people here want the Kinabatangan’s ecosystem wiped off the map. I have to do something about this horrific situation.

My wildlife enthusiasm now settled, I would’ve been satisfied seeing nothing for the rest of the trip back to the lodge. We still nailed some good species. The sun was setting and wildlife started venturing near the river. I spotted a pair of Wreathed Hornbills on a distant dead tree, our third hornbill species for Borneo. And yes I was keeping careful track of our hornbill species count. These prehistoric-looking birds are pretty badass.

Our next species of note was a troop of Silvery Langurs, this time a harem troop with a dominant male and several females with young. They were concealed in vegetation, making photography hard.

As the light faded, we watched a Storm’s Stork perched high above before returning to the lodge, more than satisfied with our finds.

We ate a delicious dinner at Melapi. This time I was able to convince my entire family to join me on the night safari. My sister was going mainly for the stargazing. Our sightings that night turned out to be primarily birds, and we saw several avian targets of mine along with some interesting finds like a one-eyed owl. Everyone was happy afterward, and I went to bed extremely satisfied with a full day of wildlife. Here are photos of the highlight species of the night:

Our final morning safari we were able to switch boats. Luckily we got a much better guide than before, who turned out to be an excellent bird spotter. My goal was to find a Rhinoceros Hornbill, a signature Bornean poster child and a truly spectacular animal. At 6am, we set off.

Apart from the hornbill, we scored with raptors. A Crested Serpent Eagle, Besra Hawk and the Jerdon’s Baza, a sought-after local specialty, were among the species we recorded.

Our guide understandably misidentified a big target for myself and basically every other birder to this region: the Bornean Falconet, the world’s smallest raptor and one entirely restricted to Sabah. It’s the size of a starling (a medium-sized songbird for you non-birders), and often perches atop tall dead trees, so it made sense why our guide thought the Javan Myna below was a falconet before further inspection. Gave me a rush of excitement, though.

I spotted Prevost’s Squirrels of the beautiful black-and-red pluto race (Callosciurus prevostii pluto) several times around the lodge. However, it was along the river that we got our best sighting of the mammal as it foraged for figs. Probably the most striking squirrel species I’ve ever seen.

Rounding a bend in the river, our guide made a pretty incredible spot–a Rhinoceros Hornbill from a tree probably well over 300 feet (100 m) away!! At first, it was hard to see, as the trunk blocked our view of the bird, but it shifted position, revealing its striking bright orange bill and casque. Fun fact: their casques turn orange due to a pigment in their preen gland oil.

After probably 10 minutes, the hornbill flew off with its mate. But before then, this amazing, threatened king of Borneo’s skies secured itself as one of my favorite birds on Earth. In my opinion, few other feathered creatures attain the majesty of the Rhinoceros Hornbill.

We cruised down a tributary of the river where a large troop of Silvery Langurs was foraging within close proximity to us. We enjoyed a lengthy photo session with the monkeys.

We arrived back at the lodge shortly after and ate breakfast, before wheeling our luggage to the dock for the speedboat ride back to Sandakan. My mom bought several souvenirs, including a cool T-shirt showing the primates of Borneo. I took photos in front of the main sign of the lodge.

We said goodbye to the Omicks and boarded the boat. For me, departing Sukau was bittersweet, but I know I’ll be back here someday. On the way back, we stopped for a medium-sized crocodile on the riverbank.

Upon arrival in Sandakan, we boarded a bus which would take us for a quick tour around Sepilok Forest Reserve’s famous Rainforest Discovery Center and then to the airport.

We only got about 10 minutes into the forest before a massive tropical downpour stopped us in our tracks atop one of the center’s metal canopy lookouts. We spotted our 5th hornbill species here, the Asian Black Hornbill, sheltering on one of the trees nearby. This was a lucky last spot for us in Borneo.

After the rain cleared, we had no time left to walk unfortunately. We headed directly to the airport, where we caught our flight back to Kota Kinabalu, and then to Singapore. A final sunset over KK concluded our weeklong trip to Borneo. In terms of birds and mammals, I recorded 67 birds and 11 mammals, which in my opinion was a decent, if not superb count.

I think each of the three posts I’ve written more than summarize and articulate my trip to Borneo; from personal observations of wildlife, to my views on the destruction of Borneo’s forests, to zoological hypotheses of mine. Therefore I feel no need to write a detailed conclusion to the trip. I’d love it if you took the time to read through all 3 posts!

What I will say is I am no more certain than ever that I’m going to work on this island someday. I’m going to protect the amazing forests that carpet Borneo and the unique wildlife within them. And I’m going to restore land that’s been devastated by the timber and palm oil industries. I hope you’ve enjoyed my recounting of this trip– it’s taken many hours over the course of two months to write about everything. I’ll end it here, and please stay tuned for more posts in the future!

-Bennett

Mammal Species Recorded (10 total, including 5 lifers)

Bornean Orangutan (Lifer) (Main target species)

Silvery Langur (Lifer)

Small-Toothed Palm Civet (Lifer)

Prevost’s Squirrel (Lifer)

Large Flying Fox (Lifer)

Proboscis Monkey

Southern Pig-Tailed Macaque

Long-Tailed Macaque

Lesser Dog-Faced Fruit Bat

Plantain Squirrel

Bird Species Recorded: (37 total, including 15 lifers)

Rhinoceros Hornbill (Lifer) (Main target species)

White-Crowned Hornbill (Lifer)

Wreathed Hornbill (Lifer)

Asian Black Hornbill (Lifer)

Storm’s Stork (Lifer)

Black-and-Red Broadbill (Lifer)

Stork-Billed Kingfisher (Lifer)

Jerdon’s Baza (Lifer)

Besra (Lifer)

Green Imperial Pigeon (Lifer)

Pied Fantail (Lifer)

Oriental Darter (Lifer)

Slender-Billed Crow (Lifer)

Mossy-Nest Swiftlet (Lifer)

White-Nest Swiftlet (Lifer)

Oriental Honey-Buzzard

Crimson Sunbird

Oriental Pied Hornbill

Buffy Fish Owl

Blue-Eared Kingfisher

Common Kingfisher

Common Sandpiper

Crested Serpent Eagle

Striated Heron

Black-Crowned Night Heron

Yellow Bittern

Purple Heron

Lesser Adjutant

Great Egret

Little Egret

Black-Nest Swiftlet

Pacific Swallow

White-Breasted Waterhen

Ashy Tailorbird

Javan Myna

Greater Coucal

Blue-Throated Bee-Eater

Leave a comment