Welcome to part 2 of my March 2023 Borneo adventure! Hopefully you’ve read through part 1 and are up to date on the beginning of the trip for some background information. This post marks roughly the middle of the weeklong vacation: day 4 and half of day 5. We had a wide range of experiences between those two days, from watching a wild mother sea turtle lay her eggs on a remote island beach, to viewing orphaned orangutans swinging through ancient, virgin jungle.

Though our priorities weren’t wild mammals or birds, I still managed to spot some cool species while enjoying the main activities. The eco-experiences we had more than made up for lack of wildlife viewing! The sea turtle experience was once-in-a-lifetime and I would love to come back and do it again someday. Without farther ado, I’ll get into my experiences during this part of my Borneo trip.

We were woken up brutally early for our flight to Sandakan on the East Coast of Sabah. Our driver pulled into the roundabout at the Hilton at an ungodly 4:30am to take us to the airport for our 6:30 flight. Breakfast, unfortunately, was out of reach until our arrival in the former capital of Sabah. Luckily, depending on wind speed and direction, Sandakan is a mere 15-45 minutes from Kota Kinabalu by air.

The reason for our early departure had to do with the scheduling of the Turtle Islands Marine Park. A single speedboat departs for Selingan Island, the ‘turtle island’ each day at 10:45am sharp, and the tour company wanted us to be there with ample time to register for our stay at the Sabah Parks office.

The sun was peeking over the mountains as we took off into the Bornean dawn. My family passed out as soon as we reached our cruising altitude. For me, it was different story. We were flying over some of the most famous conservation areas on the island, including Sabah’s last expansive rainforests, and I kept my eyes plastered on the carpet of greenery below. Though I didn’t get an up-close view of Mt. Kinabalu from the air as I’d hoped, there was still plenty to admire as we cruised over the Crocker Range, Mt. Trus Madi (the second highest summit in Malaysia), and endless swathes of logged and intact forest, the treetops sparkling in the morning sun. As we neared Sandakan, a blanket of rainclouds obscured the view of the ground for the most part. Luckily, I was still able to catch a glimpse of the mighty Kinabatangan River, a biodiversity and wildlife hotspot we travelled to later on during the trip.

One thing that was more than apparent throughout the flight was the sheer amount of environmental destruction caused by the palm oil and logging industries. Palm oil, unfortunately, is a necessary evil in Borneo as it’s a crucial part of the economies of many areas. However, to me, logging is unnecessary in Sabah— it used to be a big contributer to the economy of Malaysia but now accounts for a tiny 0.6% of the country’s GDP. Tourism, on the other hand, especially eco-tourism, makes up 7% of the economy on a good year.

This means if Sabah’s government spares its forests and the wildlife within for tourism, they’d possibly make over ten times the cash they would from cutting them down. This is only tourism we’re talking about—researchers recently found species of plants in Borneo’s rainforests that could be cures for both HIV and cancer! (see https://news.mongabay.com/2009/06/anti-hiv-and-anti-cancer-drugs-derived-from-borneo-rainforest-progressing-to-final-development-stages/ for more info)

It was drizzling when we arrived, and after our extremely quick flight and walkthrough of the Sandakan airport to grab our bags, we met up with our Borneo Eco Tours people outside. We had a great guide with us for the following two days, named Jonathan. He was super friendly and very sharp. He briefed us on the conservation activities taking place within Turtle Islands MP as well as on Sandakan, and brought us to Hotel Sandakan, near the city center, for breakfast.

I know it’s annoying that I bring up Borneo Eco Tours a lot, but this was probably one of the last annoyances I can remember that affected us. For 3 out of 4 days we were on the East Coast, we travelled through Sandakan at least once, and for at least one meal. Disappointing then, that for a city with plenty of good food options, they left us at the buffet area of a 2-star hotel on all three occasions, for hours at a time! On a positive note, though, the food wasn’t bad, there was plenty of it to go around, and it was rather nice to chill in the AC for a little while.

Sandakan actually has a bit of interesting history. It was first settled and named by a Scottish arms smuggler. Later, it grew in size to become the capital of British North Borneo by the late 19th century. In 1944, it was totally destroyed (minus 2 buildings) by Japanese bombings, and, lacking the funds to rebuild, lost its title as the colony’s capital. Kota Kinabalu, the next largest city, took its place. The high population of HongKongese immigrants, many of whom brought by the British to construct the city, have greatly influenced the architecture and culture of the city. This is why Sandakan is dubbed ‘Little Hong Kong’. Driving through, it was easy to see why! I’d even compare it to a tropical, scaled-down version of Aberdeen, a part of Hong Kong.

My poor clothing choices meant that the muggy morning weather at the ferry pier made me pour with sweat. Luckily, our boat came quite quickly. Other than a couple Chinese and European tourists, we were pretty much alone throughout our excursion to Selingan Island, which I was grateful for given that the island has limited space (capped at 50 tourists/day) and during summer, the peak season, the 20-acre island often reaches its maximum capacity of visitors.

In terms of geography, Selingan is basically a vegetated speck of sand—a coral-formed islet situated about 20 miles northeast of Sandakan in the vibrant Sulu Sea, amid a cluster of similar islands divided between the Philippines and Malaysia. Virtually all of these islands are uninhabited apart from military personnel, researchers and rangers.

At first glance, while pretty, these islands seem to be of little conservation significance. However, one may be surprised to hear that Turtle Islands Marine Park is one of the only places on Earth–and probably the only place where it happens at such a high volume–where mother Green and Hawksbill Sea Turtles come ashore nightly to lay eggs, sometimes over 50 turtles each night during peak season! Since 1977, Sabah has been active in the conservation of both of these majestic endangered species. We were all excited to see this miracle of nature up close!

There are turtle hatcheries on all 3 Turtle Islands governed by Malaysia, and rangers work tirelessly every night throughout the year transplanting all the individual eggs laid by all the individual mother turtles to an artificial, fenced-off hatchery to protect them from predators. Then they release freshly hatched baby turtles from the hatchery into the ocean. They log each egg laid, each egg that hatched, and each mother turtle who laid them as important scientific data.

Both nations have initiated conservation measures to preserve this unique area: the survival of sea turtles in the Indo-Pacific would be jeopardised if they didn’t. Tourism to Selingan Island sponsors these efforts. Visitors are allowed to watch one mother turtle laying eggs per night, and are able to assist with the release of hatchlings into the sea.

Armed soldiers are also present on the islands, to protect them from pirates from the Philippines. Interestingly, piracy and kidnappings are a risk to tourists on Sabah’s East Coast. Luckily, Selingan has a virtually impeccable safety record.

Our hour-long speedboat ride immediately cooled me off as we ripped across the jade-green shallow waters of the Sulu Sea. I got a nice hairdew from the wind whipping past. The weather had cleared and was partly cloudy, promising a day of sun on the island. We passed the city’s famous stilt village, and an area of mangrove forest on the edge of Labuk Bay known for its Proboscis Monkey population. As we entered open sea I spotted a lone Little Tern tailing our boat.

When we neared the island chain, it reminded me of the Maldives or South Pacific with its many flat, lush islands and islets fringed with white sand beaches and turquoise reefs. We landed at Selingan’s beach around 11:30, and I helped carried our luggage across the stretch of sand, up a trail leading to Park HQ. We checked in and walked over to our visitor chalets, past the ranger’s quarters, hatchery and army barracks. The accommodation was basic but more than decent for an uninhabited island, with working AC and comfy beds.

After lunch and a briefing from a park ranger, we spent the remainder of the day exploring the island and snorkelling. The reefs around Selingan weren’t nearly as impressive as the ones at Tunku Abdul Rahman MP on the West Coast. Coral diversity was rather low and few coral massifs were present, and in turn the fish diversity wasn’t nearly as high. I still saw some interesting things. A huge rainstorm struck the island while I was snorkelling, but by the time I finished it had cleared. Along the beaches of the island were signs of turtle activity in the form of dug-up nests and tracks.

As per my tradition in tropical regions, I plucked a couple coconuts from the ever-present palms and stayed hydrated by cracking them open on rocks and drinking the delicious water inside. I went for another swim later in the day. For the most part, I was on my own during our time on Selingan.

I know we were here for sea turtles, but with so much time to kill before nightfall, I wanted to do some exploring of the island’s biota. Small islands often possess unique ecosystems, and this was no different on Selingan. The plants were more or less similar to anything you’d find in coastal ecosystems around Southeast Asia, but the animals were a bizarre blend. Monitor lizards were the apex predators, chicken-like groundbirds were the dominant terrestrial herbivores and insectivores, and pigeons were the primary fruit-eaters and seed dispersers. Many animals indirectly or directly depend on the turtles for food, in the form of their eggs and hatchlings.

Few tourists to the island take note of the land animals here, but they were fascinating to me. Selingan is only 9 or so miles from the mainland, yet a mere sprinkling of Bornean creatures have settled its shores since its formation several milennia ago. Anyway, here are some of my cool finds:

While checking in, I got a view of a unique animal Jonathan informed me about, the Philippine Megapode.

I was able to share Selingan with these awesome birds for the next 24 hours, watching their antics. The megapodes are a rather primitive group of gamebirds restricted to Southeast Asia and Australasia. They’re about chicken-sized and walk on the ground. Philippine Megapodes, for reasons I’m not entirely sure of, are restricted to tiny offshore islands around Borneo, not being found on the mainland. Seeing these guys in total abundance here, filling the niches of different species found on the mainland, was almost like stepping into a lost world!

There was limited bird diversity on Selingan, but the pigeons and doves outnumbered all other small to medium-sized birds. In the forest, Emerald Doves, which are uncommon on the mainland, were abundant. Their bright-green wings were striking! Pied Imperial Pigeons, island and coastal nomads that are scarce in other places, were also common. My guess is without other fruit-eating and seed-eating birds or mammals to compete with them, the pigeons and doves have become the dominant seed dispersers and frugivores here and are therefore found in higher numbers than elsewhere.

Aside from a couple monitor lizards, shorebirds, skinks and a Brahminy Kite, I’d seen most of the wildlife the island had to offer. It was interesting to ponder the origins of the creatures and the niches they filled here.

I met up with my family before dinner and we watched the sun set on the beach. After dinner, Jonathan gave us a thorough briefing on our activities that night as well as info on the park and the turtles themselves. Green Sea Turtles lay an average of 110 eggs per clutch, in a pit they dig a couple feet deep. They bury the eggs and return to the sea.

The temperature of the sand determines the sex of the offspring, hotter, (87+ degrees) means females while cooler, (below 82 degrees) means males. Below or above a certain temperature, the embryos will die. After around a month, the eggs hatch and the babies scurry to the sea, as fast as they can to avoid predators.

We proceeded to wait within the park HQ for a sea turtle to come ashore as the blackness of night settled.

After an hour of waiting anxiously, we got the call! It was “Turtle Time”. A mother Green Sea Turtle had come ashore nearby and had started laying her eggs. Sometimes this first landing is past midnight, so we were lucky it was so early. Jonathan and a park ranger led us tourists to the beach using headlamps. Suddenly, in front of us was a massive, prehistoric animal. The turtle was in a trancelike state while she laid her eggs. I’d seen sea turtles plenty of times before snorkelling and diving, but never this close and never on land.

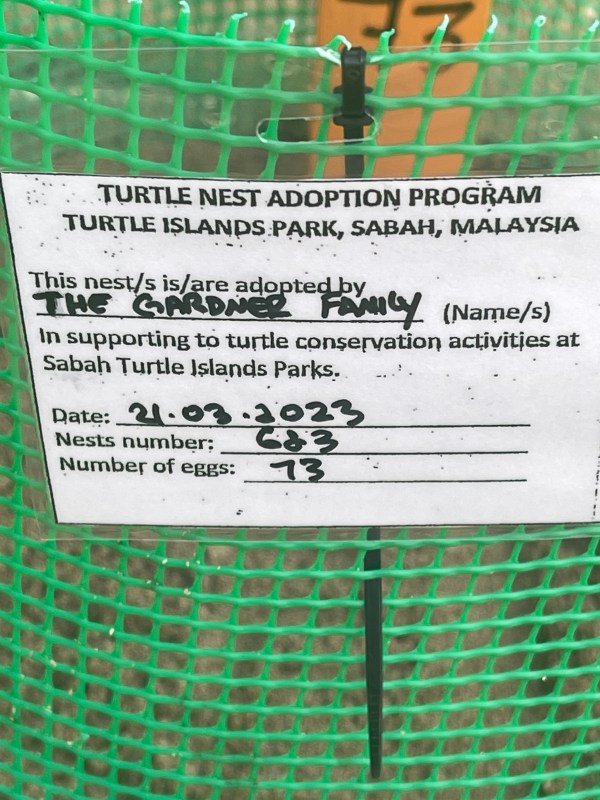

You really get some perspective for how big and incredible these reptiles are! It far exceeded me in weight, and it’s carapace alone was measured at over 1 meter (3.3ft) long. We watched speechless as a ranger collected each watery, golfball-like egg that she laid (all 73 of them) and placed it into a bucket. Jonathan guided us through the whole experience. We were not to disturb the mother while she laid her eggs.

After probably 10 minutes she was finished. I felt a little bad for the hapless animal burying what she thought was a full clutch of eggs despite all of them having been removed! One thing about this magical experience was I learned that sea turtles are powerful, fast diggers. We were allowed to gently touch the mother during this time, for a short while before we had to depart. Sea turtles are incredibly smooth.

Altogether it was an unforgettable experience with these peaceful giants. We watched the ranger bury the eggs at the hatchery and afterwards we transferred once again to the beach to assist in the release of baby sea turtles. They are adorable. We were all rooting for them as they raced for they sea as fast as possible! Altogether, that night marked one of my favorite-ever wildlife experiences, and a glimpse at the mammoth conservation efforts being put forth by Sabah Parks to save sea turtles from extinction. These guys are doing amazing work, and it’s my sincere hope that they’ll continue it into the far future!

Later that night, my family decided to ‘adopt’ the clutch of eggs by donating a sum of money to the conservation effort here. I was really happy we did this! Fingers crossed those babies make it to adulthood, but the chances are slim…..

The next morning we were up early (again…) to catch our speedboat back. Apparently 19 mother turtles had come ashore the night previously, which isn’t even that high a number for the island. We arrived in Sandakan early, and drove through the countryside surrounding the city on our way to the Sepilok sanctuaries next to Sepilok Forest Reserve, a 40 sq km (15 sq mile) square-shaped patch of wondrous virgin dipterocarp forest. Borneo has the tallest rainforests in the world as it possesses the highest diversity of dipterocarps–the world’s tallest tropical trees–on Earth. Virgin forests like Sepilok are places where the trees reach these lofty heights; some over 300 feet tall!

The Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Center and Sun Bear Conservation Center are the two main sanctuaries in Sepilok, located right next to each other. They take in abused, orphaned or rescued Bornean Orangutans and Sun Bears and either rehabilitate them back into the wild, or give them a permanent home at the center.

We drove through a meshwork of palm oil plantations and rural settlements before reaching the orangutan center. We had to wait until 9am for the center to open, which gave us time to stretch our legs. From the parking lot, I was immediately captivated by the immensity of the trees in the surrounding rainforest. They must’ve soared well over 150 feet up off the forest floor, dominating all other structures in their vicinity. You really don’t get perspective on just how big ancient dipterocarp trees are until you rub noses with one. Jonathan pointed out specimens of Shorea that he said could be over 300 years old. It was pretty breathtaking!

We headed over to the ticketing office to wait for the sanctuary to open along with a large number of fellow tourists. Jonathan spotted a soaring Crested Serpent Eagle nearby with his keen eye. While a common species in Borneo’s rainforests, it’s always great logging a new species of raptor.

After collecting our tickets, we waited eagerly for the gates to open (well, maybe that was just me). Once the sanctuary opened, we joined the flood of other visitors and made our way down a boardwalk into the dense virgin forest.

60 years ago, when the sanctuary was founded, Bornean Orangutans roamed over 100,000 miles² of Borneo’s lowland rainforests (or over 1/3 of the island). This was the beginning of the era of destructive commercial logging there. Since then, 60% of orangutan habitat has been levelled and a shocking 50% of orangutans have disappeared. Today, less than 100,000 and probably fewer than 50,000 remain, in scattered subpopulations around the island. Sabah is a stronghold for this species, with enough protected forest to sustain its 11,000 fire-orange great ape inhabitants.

The sanctuary has done great work, having successfully rehabilitated 600 orangutans into the wild. As Sepilok Forest Reserve has already reached its carrying capacity of wild orangutans, the apes are now released into the much larger Tabin Wildlife Reserve to the southeast. Jonathan taught us about the sanctuaries’ work as we made our way into orangutan territory. We caught our first glimpse of one of the well-furred arboreal apes sitting on a railing. We cautiously made our way around the inquisitive young male.

We walked to an air-conditioned indoor viewing area overlooking one of the center’s primary feeding platforms. Sanctuary staff had left piles of greens and fruits for the orangutans. Pretty soon, a number of these graceful primates were materializing out of the forest and making their way over to the platforms to nab some treats. Most were orphaned adolescents.

One greedy individual grabbed as many cabbage leaves as he could possibly muster, then moved off to a secluded platform to feed.

As the apes squabbled, a wild troop of Southern Pig-Tailed Macaques from the forest appeared for their breakfast. The troop was primarily composed of females and young led by a beautiful alpha male. The male effortlessly usurped the platform from the orangutans, and chased many of them back into the jungle.

You might be surprised that a single monkey was able to repel hugely strong, human-sized apes, but this guy was an absolute unit—complete with big muscles, massive canines, and thick, golden fur. My dad and I joked that he probably spends more time in the gym than both of us combined! For a monkey, he was an intimidating sight to behold.

After the orangutans departed, we proceeded to walk to an outdoor viewing platform. Along the way, Jonathan spied a Cream-Colored Giant Squirrel, one of the largest squirrels on Earth, sprawled out on a tree branch. It was of the local Sandakan race, and differed in patter and color from other members of its species elsewhere.

There were literally hundreds of tourists crowding around the outdoor feeding platform, awaiting the arrival of more mature orangutans from the forest. We had to wear masks in the sanctuary to avoid transferring pathogens to the apes. The bodyheat generated by all these people compacting together in a confined space, coupled with the sultry midmorning jungle weather, was causing us a lot of discomfort.

Food was placed down by a reserve staff and we watched the orangutans arrive one by one. This time, the resident macaques didn’t deter the apes. Though we didn’t see a fully-matured ‘flanged’ male (characterized by a flattened, disc-like face and enormous body which symbolized dominance) as I’d hoped, we did see a wild mother and baby that had arrived from the nearby forest reserve.

The heat became too oppressive to stay at the platform after about 20-ish minutes, and we departed the sanctuary shortly after. It was eye-opening seeing the forefront of the conservation efforts directed at these great apes. For our next activity, we had the option of waiting half an hour to watch a conservation video about the orangutans, or visiting the nearby Sun Bear Conservation Center earlier than planned. We chose the latter option, and walked 5 minutes to the second sanctuary, the only one of its kind.

As we neared the top of the stairs leading to the viewing platform containing the bears, Jonathan came through again with the wildlife spotting, finding a brilliant male Crimson Sunbird that dashed away as soon as we saw it. Back to the bears.

The center was founded in 2008 by wildlife biologist Dr. Wong Siew Te, a passionate advocate for the world’s smallest bear. No bigger than large dogs, these poorly understood and fierce yet adorable animals are threatened by habitat destruction and illegal body part harvesting for the traditional medicine trade. Specifically an evil product known as bear bile, taken from the gallbladders of bears. Check the link out for more info on this horribly inhumane trade: https://www.animalsasia.org/intl/end-bear-bile-farming-2017.html#:~:text=Bear’s%20bile%20is%20extracted%20using,their%20gallbladder%20through%20their%20abdomen.

Borneo’s forested interior contains one of the world’s largest remaining populations of Sun Bears, making the island an ideal choice for a rehabilitation center. Sun Bears are more arboreal than any other bear—in the wild they sleep in nests they build in the jungle canopy like orangutans—and spend much of their time in the trees. Around 40 live at the center, in several fenced-off paddocks within the jungle where they can interact with other bears within their natural habitat.

The center takes in orphaned bears (much like the orangutan sanctuary), and either gives them a permanent home if they are unable to return to the wild, or rehabilitates them into the rainforest of Tabin. As we walked around the Jurassic Park-style elevated walkway that circumvented the bear paddocks below, we watched the Sun Bears scuffle with one another and feast on fruit. Almost dog-like in facial structure and stature, they’re quite vocal animals as well. When two individuals fought over food, one let out a bellowing roar!

The Sun Bear and orangutan sanctuaries are two of Borneo’s most successful conservation stories, educating millions of tourists annually about the threats facing these two charismatic animals and rehabilitating various individuals back into the wild.

These past 2 days around Sandakan showed me that people concerned about the future of Borneo’s incredible wildlife, both marine and terrestrial, have already done outstanding things to conserve it. These people—from the rangers at Selingan to the staff at Sepilok—are true inspirations myself and others. Because instead of ignoring or pretending to care about the biodiversity crisis affecting all areas of the globe, not just Borneo, they have dedicated their lives to stopping it.

In addition, you will not get a better opportunity anywhere else on Earth to be as up-close and personal with sea turtles as they lay their eggs as you are on Selingan, whilist still being respectful of the creatures. As for orangutans and Sun Bears, no place is better than Sepilok to see them in their natural habitats. I highly recommend that anyone, from globe-trotters to regular people, planning their next vacation to Borneo, take the time visit both of the Sandakan Sanctuaries and also Seligan Island. It’s well worth the money!

With that, I close this blog post. Stay tuned for the 3rd and final chapter of my Borneo adventure!

Bird Species Recorded: (13 total, including 4 lifers)

Philippine Megapode (Lifer)

Little Tern (Lifer)

Crimson Sunbird (Lifer)

Crested Serpent Eagle (Lifer)

Emerald Dove

Pied Imperial Pigeon

Chestnut Munia

Yellow-Vented Bulbul

Pacific Reef Heron

Olive-Backed Sunbird

Brahminy Kite

Eurasian Tree Sparrow

Mammal Species Recorded: (3 species total, including 1 lifer)

Cream-Colored Giant Squirrel (Lifer, local endemic race)

Southern Pig-Tailed Macaque

Long-Tailed Macaque

Leave a comment